Unit economics form a foundational building block of business. The reality is that many business owners don’t know what they are or are only familiar with the concept. What is Unit Economics, and how can it help you and your business?

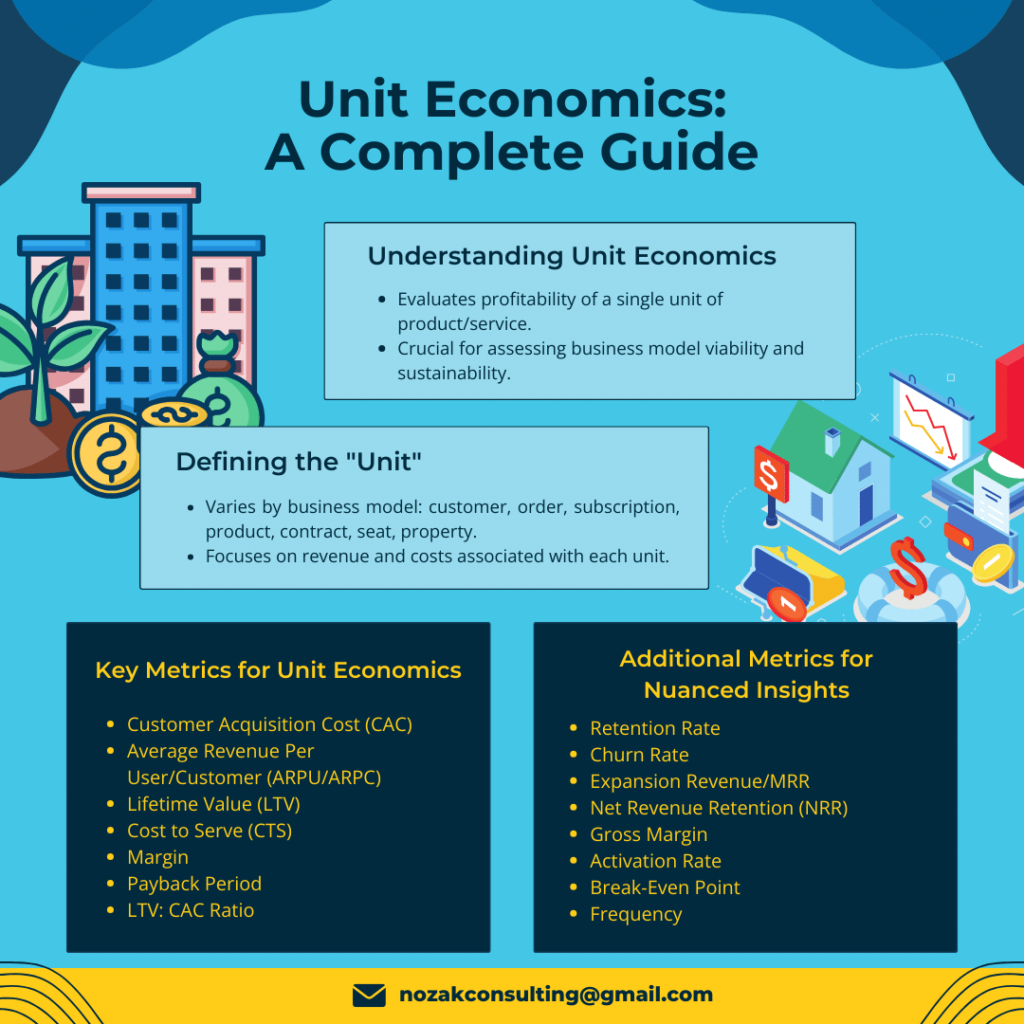

What Is Unit Economics?

Unit economics refers to the fundamental financial metrics that evaluate the profitability of a single unit of a product or service. It’s a way to dissect and understand the direct revenues and costs associated with one unit of sale. Unit Economics is great for offering insights into the viability and sustainability of a business model.

By examining unit economics, companies can determine whether they make or lose money on each transaction. This is after accounting for variable costs. Analysis like this is crucial for startups and scaling businesses. Achieving positive unit economics often signifies a sound business model, paving the way for sustainable growth and profitability.

Negative unit economics could indicate structural problems that increasing sales volume might not offset. It can point you in the direction of any variable cost that is dragging down your net return.

What Is a Unit?

In unit economics, a “unit” typically refers to the fundamental element upon which the business model operates and earns revenue. The exact nature of this “unit” depends on the specific business model and industry.

For many businesses in the world of startups and tech, the “unit” is often an individual customer or user. The term “unit economics” in this context refers to understanding the profitability of serving that individual customer.

The “unit” could be different based on the nature of the business:

1. Customer/User

This is common for many business-to-consumer (B2C) or business-to-business (B2B) models, where metrics like Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Lifetime Value (LTV) become central.

2. Order/Transaction

For businesses that are transactional in nature, like e-commerce, each individual order or transaction can be considered a “unit.”

3. Subscription

For subscription-based businesses, each subscription (e.g., a monthly or annual subscription to a service) can be the “unit.”

4. Product Unit

In traditional manufacturing or retail, the “unit” could be an individual product. In a shoe manufacturing business, the unit economics might revolve around the cost of producing one pair of shoes versus the revenue from selling that pair.

5. Contract/Project

For businesses that operate on a project or contract basis, such as construction or consulting, each contract or project can be seen as a “unit.”

6. Seat or License

For software companies selling on a per-seat or per-license model, each seat or license can be the “unit.”

7. Property/Asset

In industries like real estate or hospitality, each property, hotel room, or asset might be the “unit.”

The central idea behind unit economics is to break down and understand the revenue and costs on a per-unit basis, thus allowing businesses to ascertain the viability and scalability of their model.

Regardless of what constitutes a “unit” in a given business, the goal is to understand the direct revenues and costs associated with that unit. Business owners and operators can then make informed decisions about scaling, pricing, marketing, and other aspects of business operations.

Key Metrics and Fundamentals for Unit Economics

Unit economics refers to the direct revenues and costs associated with a particular business model on a per-unit basis. Here are the key metrics involved in unit economics:

1. Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

This is the cost incurred to acquire a single customer. It includes marketing expenses, advertising, sales team expenses, and any other costs directly associated with attracting a new customer.

2. Average Revenue Per User/Customer (ARPU/ARPC)

This is the average revenue generated from a user or customer over a specific period.

3. Lifetime Value (LTV)

This is the total net profit a company expects to earn from a single customer over the entire life of that customer’s relationship with the business.

4. Cost to Serve (CTS)

This is the cost associated with delivering the product or service to the customer. It includes expenses like hosting, support, operational costs, etc. For SaaS (Software as a Service) businesses, this is often referred to as the “Cost of Goods Sold” (COGS).

5. Margin

This is the profit generated from a single unit after all variable costs are subtracted. It can be represented as a percentage:

6. Payback Period

This represents the time it takes for the revenue from a customer to cover the CAC. The shorter the payback period, the quicker a company can reinvest in acquiring new customers.

7. LTV: CAC Ratio

This is a ratio that compares the lifetime value of a customer to the cost of acquiring that customer. A ratio greater than 1 indicates a profitable customer acquisition, while a ratio less than 1 suggests that the cost of acquiring customers might be unsustainable.

Understanding these metrics is crucial as they provide insights into the profitability of each customer and indicate whether the business model is scalable. A high CAC compared to LTV suggests the business might be spending too much on customer acquisition. That is when compared to the value they get in return.

Conversely, a high LTV compared to CAC indicates a potentially scalable and profitable business model. To get a multi-dimensional view of the business and unit economics, here are a few additional metrics that can help fill in the picture.

Additional Metrics for Unit Economics

While the previously mentioned metrics are foundational for understanding unit economics, there are additional metrics and variations that can provide more nuanced insights depending on the nature and stage of the business. Here are some more unit economics metrics and considerations:

1. Retention Rate

This measures the percentage of customers that continue to use your product or service over a specific period. A higher retention rate usually leads to a higher LTV.

2. Churn Rate

This is the opposite of retention. It represents the percentage of customers who stop using your product or service over a specific period. High churn can significantly reduce LTV.

3. Expansion Revenue/MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) Expansion

For subscription businesses, tracking new sales and how existing customers expand their spending is vital. Expansion revenue accounts for upsells, cross-sells, and any other additional revenue from existing customers.

4. Net Revenue Retention (NRR)

This metric considers both churn and expansion revenue. An NRR greater than 100% indicates that expansion revenue exceeds lost revenue from churn. Which is a positive sign for SaaS and subscription-based businesses.

5. Gross Margin

Similar to margin, but it takes into account all costs directly related to producing the product or service but excludes indirect costs like sales and marketing.

6. Activation Rate

Especially important for freemium or trial-based models, this measures the percentage of users who take a desired action (e.g., sign up for a paid account after a free trial).

7. Break-Even Point

The point where the net profit, after fixed costs and variable costs have been subtracted, is zero. This tells a business how many units of a product or service they must sell to cover costs.

8. Frequency

This metric measures how often customers buy within a given period, which is especially important for businesses that rely on repeat purchases.

It’s essential to understand that while individual metrics are important, looking at them in isolation can be misleading. The interplay between these metrics, and context based on the industry, is often a better indicator of the overall unit economics and business health.

Your Business and Unit Economics

There are many metrics associated with Unit Economics, and all of them play a role. Depending on what type of business you are running will determine how you utilize them. The more metrics you track, the more complete your picture of the overall profitability and scalability of your business will be.